Here comes the 21st century’s first big investment wave. Is your capital strategy ready?

The world will see a once-in-a-lifetime wave of capital spending on physical assets between now and 2027. This surge of investment—amounting to roughly $130 trillion1 —will flood into projects to decarbonize and renew critical infrastructure.

But few organizations are prepared to deliver on this capital influx with the speed and efficiency it demands. Many are burdened with inefficient supply chains and outdated project delivery systems. For one thing, constructing and justifying the cost of a physical asset such as a manufacturing plant is much more difficult than it was decades ago, given inflation, rigorous sustainability requirements, and rapid changes in technology and regulations. Adding to the complexity, the next generation of assets needs to be “set and forget”: the high cost of building them must be offset by lower operating costs.

Delivering on an investment of this magnitude is no longer just the province of IT or engineering experts. Responsibility for end-to-end capital spending projects may need to move squarely into the domain of the CEO and C-suite leaders, who must engage on the portfolio of capital projects to ensure that the CFO is planning appropriately for increased capital outlays for years to come—which may require potential amendments in capital financing and allocation—and for the associated risks in delivery. Boards and shareholders will be particularly interested in the return on such a massive investment and its likelihood of success in achieving the business’s goals.

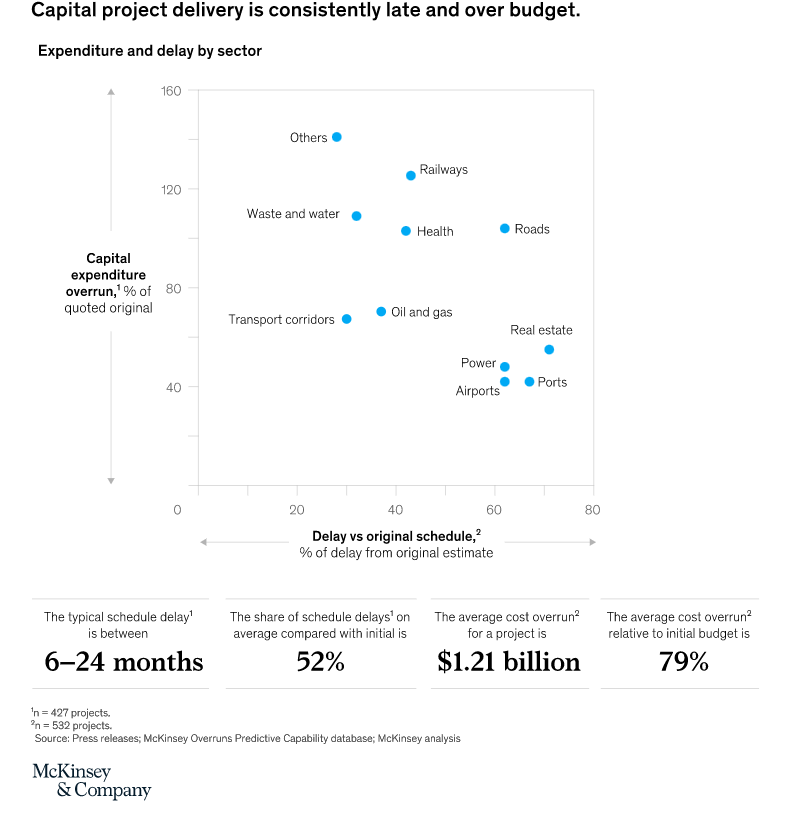

For decades, capital project leaders have relied on practices that attempt to optimize individual investments, such as a nuclear power plant, an oil refinery, or a pipeline. Cost overruns approach $1.2 billion on the average project—79 percent of the initial budget—and delays run six months to two years. This approach will not work for new decarbonization and sustainability investments, where groups of similar projects (such as wind farms and solar parks) are delivered repeatedly over a long period of time and require much better performance than in the past. A project-centric approach also will not work for decarbonizing existing assets, which is a capital-intensive effort that requires long-term planning. Low-carbon projects involve different considerations from traditional capital projects: for example, building a renewable-energy facility may also require building energy-storage capacity to supply backup power if needed. The growing threat of climate risks such as storms and floods means that companies may need to be careful about how they design assets and where they locate them. That may rule out siting a chemical plant near a coastline so it has easy access to a shipping terminal.

A more reliable approach is a portfolio-synergistic strategy in which planning is top-down, with the goal being to develop and deliver each project so that the overall results of the capital spending portfolio are optimized. Implementing this new strategy would be a major business challenge, requiring savvy stakeholder management, capital markets expertise, and an understanding of complex approval processes, as well as the ability to source the necessary talent, navigate supply chain obstacles, and communicate a long-term vision and goals.

That’s a long list of difficult tasks, and organizations are still grappling with it. But some companies are bringing a holistic, CEO-led approach to their capital strategies, leveraging data and analytics to improve the process from design to delivery. In this article, we discuss how these emerging best practices can foster capital excellence and value-creating growth, as well as deliver a competitive advantage for first movers.

A historic investment surge in mobility, power, and buildings

The bulk of capital investment worldwide will go into climate action and sustainability projects, as governments and private-sector organizations move to reduce climate risk and meet the Paris Agreement target of net-zero emissions of greenhouse gases by 2050.2 Ninety-three percent of CEOs say that sustainability issues are important for the future success3 of their business, and 54 percent expect sustainability to be embedded within the core business strategies4 of most companies in the next decade. Governments are imposing carbon taxes and setting decarbonization regulations—for example, in July 2021 the European Commission adopted the Fit for 55 package, a series of legislative proposals to reduce net greenhouse-gas emissions by at least 55 percent by 2030.5

Sustainability and decarbonization will receive substantial investment. Reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 requires $9.2 trillion in annual average spending on physical assets, $3.5 trillion more than today, according to a new McKinsey report (Exhibit 1).

Three sector groups—mobility, power, and buildings—would account for approximately 75 percent of the total spending on physical assets in this net-zero scenario. Mobility would account for about 40 percent of the spending, including investments in electric vehicles (EVs) and charging infrastructure. Energy would account for 20 percent and would include developing renewable-energy capacities (for example, solar plants and wind farms), upgrading transmission and distribution networks, and investments in carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies.

Semiconductor supply chains. The COVID-19 pandemic exposed many supply chain vulnerabilities, particularly those in the booming semiconductor industry.6 As a result, organizations around the world are investing heavily in projects that would help them become more self-sufficient in chip production. In the United States, the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) for America Act includes $52 billion for domestic semiconductor production. In January 2022, Intel announced a new $20 billion factory outside Columbus, Ohio; the company also expects to construct a multibillion-dollar chip plant in Germany, with supporting facilities to be built in France and Italy.7 Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company plans to build new wafer fab plants outside Taiwan.8

Public infrastructure. Globally, governments are investing in public infrastructure and services to drive economic recovery (Exhibit 2).

For instance, in Europe and the United States, significant funding has been allocated to infrastructure projects across numerous asset classes. In November 2021, the US Congress passed the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law,9 which appropriates $1.2 trillion (including $550 billion in new funding) to rebuild the country’s road and rail infrastructure, deliver high-speed internet access to all Americans, provide greater access to clean water, invest in new clean-power technologies, and improve the nation’s overall resilience to the effects of climate change (Exhibit 3).

In Europe, to deliver on the Green Deal’s goal of climate neutrality by 2050 and emerge stronger from the pandemic, the European Union has launched the largest stimulus package ever: €807 billion labeled as NextGenerationEU.10 As of March 2022, the Recovery and Resilience Facility, which funds NextGenerationEU initiatives, has accepted 22 proposals from member states, about 40 percent of which support climate objectives.11

The operational challenge

The anticipated capital investment in assets is large, but so are the obstacles to its implementation, including major shortages of labor, equipment, and raw materials. Delivering capital projects is already a challenge. Across industries, projects experience severe cost overruns and delays. As noted earlier, overruns approach $1.2 billion on the average project—79% of the initial budget—and delays can range from six months to two years. The added burden of growth in capital spending will place more stress on a broken system, with project execution failing to keep pace with anticipated growth (Exhibit 4).

Skilled-labor shortages and rising costs have become a major issue in several markets. For example, about 41 percent of the current US construction workforce is expected to retire by 2031, and current construction wage trends far exceed recent rates. In industries such as metals and mining, sustainability challenges will impose additional pressure to produce raw materials to accelerate decarbonization.

Severe capacity constraints are preventing many assets from being built on schedule. For instance, to meet its requirements for an additional 600 gigawatts of onshore windmill power by 2030, Germany would need to build an estimated 200,000 assets. But availability of space, raw materials, equipment, and labor falls far short of the goal, and approvals are slow. Addressing these issues will be a daunting task, requiring foresight and collaboration among governments, company boards, asset owners, contractors, suppliers, and service providers.

Strategies for capital excellence

Despite these constraints, companies in various industries are already taking steps to optimize capital investment for the new breed of assets. While the basics of effective capital management still apply to all projects, the experiences of these firms reveal some new strategies to consider:

Incorporate sustainability as a strategy.

Establish a well-orchestrated ROIC scheme.

Ensure that technical and engineering expertise is represented in the C-suite.

Create asset-based ecosystems.

Deploy advanced analytics for better capital planning.

Incorporate sustainability as a strategy. This means making green operations integral to investment in and management of assets, as these organizations have done:

An agriculture and food company embarked on a top-to-bottom capital excellence transformation journey with a strong focus on sustainability and quality, including locating and building plants with the lightest consumption of resources possible. The company reviewed its supplier selection, operating model, and level of vertical integration and set up performance management tools to track sustainability implementation.

Construction industry leaders are playing a vital role in decarbonizing materials such as cement and concrete by focusing on three elements: redesign, reduce, and repurpose, which can achieve up to 48 percent net reduction in emissions.

Oil and gas players are shifting their portfolios toward greener assets.12 For instance, Shell expects to cut the number of its refineries from 13 to six,13 freeing capital to invest in more sustainable businesses14 such as electricity, renewables, and services (for example, EV charging). Similarly, BP has embarked on a net-zero journey,15 and TotalEnergies has conducted several acquisitions in electricity retail, renewables, and the future of mobility.16

Pure-play start-ups are building eco-friendly businesses, including purpose-built green assets such as battery factories, renewable-energy production facilities, green hydrogen electrolyzers, and even green steel.17

Establish a well-orchestrated ROIC scheme. Given the amount of capital available, organizations are at the risk of spending too much for a low return. A robust ROIC plan helps to avoid affecting the company’s performance in the long run, especially given that ROIC most likely will be the ultimate key performance indicator driving enterprise value in the capital markets. Today’s investment choices—where, when, and how to invest in and build physical assets—will have a significant impact on an organization’s performance and ability to survive in the coming years. Here are some examples of long-term ROIC planning:

A gas company in Europe conducted a thorough assessment of the impact that the European Green Deal would have on its assets and business. New regulation would lead to a 5 percent loss of its business in the next five years, a 30 percent loss in the next 15 years, and a shutdown by 2050. Based on this projection, the company developed a 15-year plan to invest in new businesses based on the capital available, the organization’s capabilities, and the time it would take for the new regulations to have an impact.

A food company assessed several potential locations to build its new factory, balancing variables such as the price of carbon compared with the distance to its suppliers and distribution centers. In addition, it performed a complete value improvement analysis to determine the scope of what needed to be built and maximize the ratio of value delivered to the capital spent.

Ensure that technical and engineering expertise is represented in the C-suite. Today, the C-suite tends to be dominated by business leaders. Given the technical challenges ahead and the importance of decisions to be made on assets that will affect future growth, companies may want to consider bringing engineering and technical expertise to the board, appointing chief technology officers (CTOs), and strengthening internal capabilities.

For instance, a company that wanted to enter the telecommunications market as quickly as possible assigned project management for its network deployment to the CTO as a direct responsibility. The project was deemed too strategically important for the deployment to be managed by a contractor.

Create asset-based ecosystems. Shifting away from individual projects, companies by asset class could create successful working communities of contractors, subcontractors, suppliers, and technology providers. These ecosystems could be built on a shared culture of continuous improvement and a drive toward the technical limit of what is feasible. They could also be a key enabler to solve the challenges related to resource shortages and could allow the development of joint road maps to meet long-term cost and delivery targets rather than create bespoke projects starting from scratch each time. Such ecosystems are already evolving:

Tesla is building its leading-edge “gigafactories” to expand Europe’s battery capacity and unlock the energy storage, grid utilization, and mobility strategies needed to achieve decarbonization. Strong collaboration, partnerships, and commitments among internal and external stakeholders may be necessary to scale battery capacity at the required rate.

Similarly, in public infrastructure, utility companies have started to shift toward a long-term partnership model. They offer contractors the opportunity to bid for a portfolio of projects instead of a single project, with a commitment to provide work for several years, guaranteeing them revenue for a long period of time. This type of partnership builds trust between owners and contractors, allows the development of joint and repeatable operating models, and offers an incentive for contractors to supply relevant resources and skills to satisfy the contract terms. As a result, after a learning curve, projects are delivered faster, with greater accuracy and less owner involvement.

Deploy advanced analytics for better capital planning. Analytics-driven insights have the potential to transform the way organizations work on capital projects and portfolios, targeting key business decisions across the full project development life cycle. Companies can leverage analytics tools at any stage of a project, from capital portfolio optimization to planning optimization and real-time process tracking. For example:

At its Kalinganagar plant in India, Tata Steel deployed advanced analytics in a three-phased project to improve the facility’s performance, winning acclaim for becoming one of the leaders in the adoption of Fourth Industrial Revolution technologies.

An engineering firm wanted to understand drivers of overall profitability to increase profits in three years. Using advanced analytics, the firm assessed data from thousands of projects over the past six years and was able to identify patterns that led to increases in project profitability. Analytics also significantly improved forecasting accuracy over the firm’s existing business tools.

An oil and gas company leveraged AI-based analytics to forecast project duration and identify high-risk activities for a project that had been delayed more than a year. A machine learning (ML) algorithm was trained to assess historical performance across projects and schedules. The ML tool predicted total project delay with near-total accuracy and identified key risk activities. It had the potential to generate millions of dollars in savings if used during project execution.

Fuente: www.mckinsey.com